The Terraform “Wrapper Tax”: Why I Stopped Abstracting Multi-Cloud Modules

The dream of “Write Once, Run Anywhere” Infrastructure as Code has mutated into a nightmare of technical debt. It’s time to embrace verbose, native code.

Around 2018, many of us in the DevOps space shared a collective dream. We believed that with enough clever Terraform coding, we could abstract away the underlying cloud provider completely.

We envisioned a utopia where a single module "compute" could deploy a VM to AWS, Azure, or GCP just by flipping a variable like provider = "aws". We imagined a world of perfect code reuse, where infrastructure was truly commoditized.

By 2025, that dream has largely curdled into a reality of crushing technical debt.

As we highlighted in our broader analysis of Hybrid vs. Multi-Cloud Engineering Realities for 2025, the operational friction of managing multiple clouds is already immense due to data gravity and identity sprawl. But one of the biggest sources of friction is often self-inflicted: over-abstracting Terraform modules.

This introduces what I call the “Wrapper Tax”—a heavy toll paid in feature lag, debugging complexity, and cognitive load.

Here is why advanced infrastructure teams are abandoning the “Universal Module” and returning to verbose, native, side-by-side Terraform blocks.

The “Lowest Common Denominator” Problem

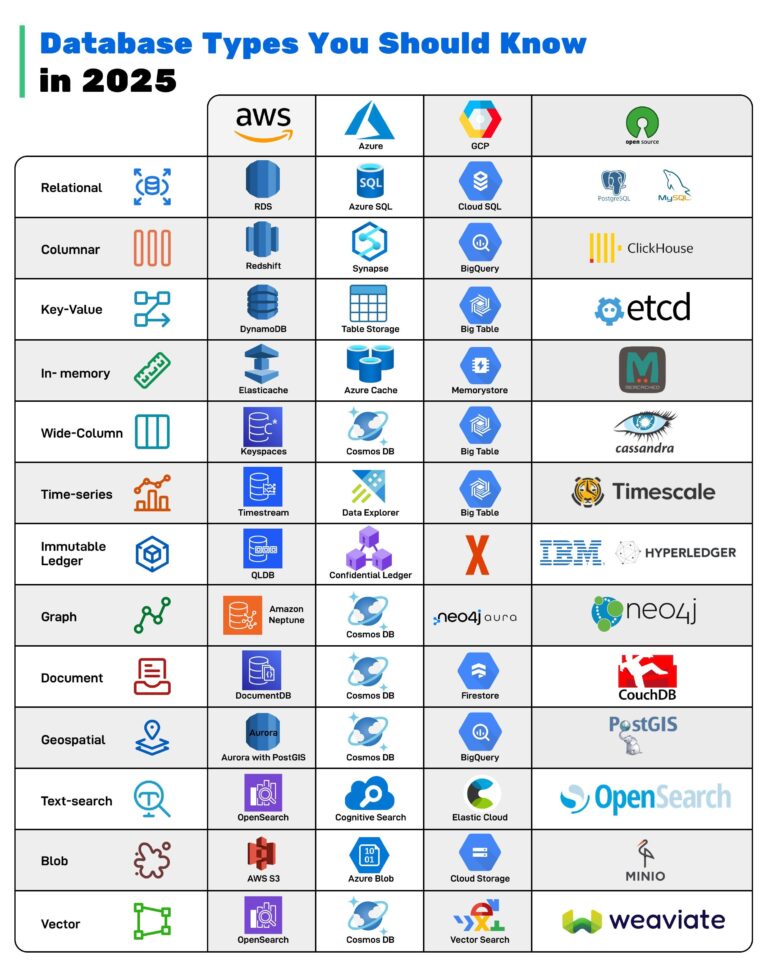

The fundamental flaw in trying to write a single module for multiple clouds is that AWS, Azure, and GCP are not isomorphic. They are not interchangeable parts.

While they all have “virtual machines” and “load balancers,” the implementation details differ wildly.

- AWS relies heavily on stateful Security Groups applied at the instance network interface level.

- Azure uses Network Security Groups (NSGs) which are generally stateless and are best applied at the subnet level.

If you try to write a single generic module called module "firewall" to handle both, you have two bad choices:

- The LCD Trap: You only expose the features that exist exactly the same in both clouds (the “lowest common denominator”), crippling your ability to use advanced security features unique to either platform.

- The Complexity Trap: You write dozens of

dynamicblocks and convoluted ternary operators (count = var.cloud == "aws" ? 1 : 0) inside the module to translate your generic inputs into provider-specific API calls.

In the second scenario, you haven’t simplified anything. You’ve just built a brittle, bespoke API translation layer on top of Terraform that only your team understands.

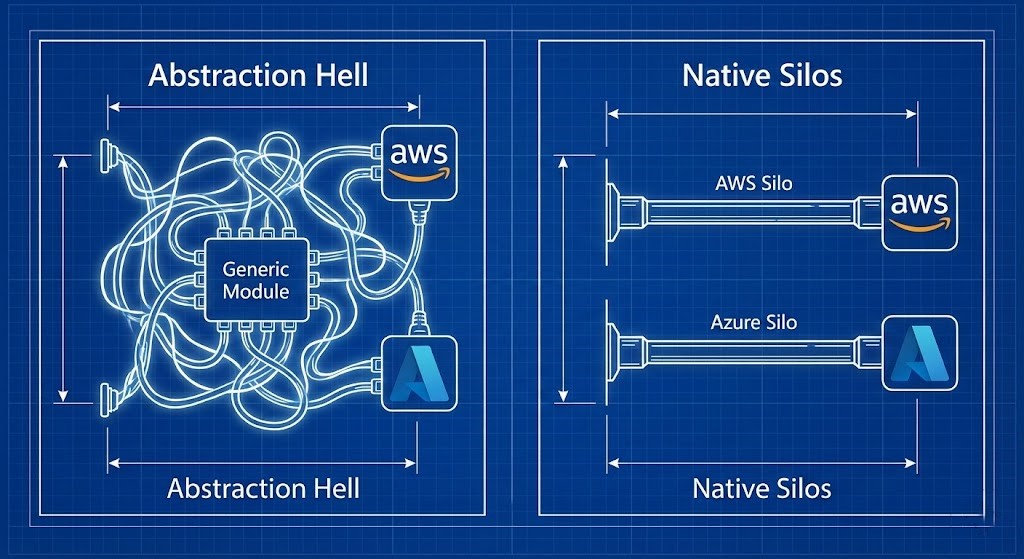

Visual Engineering: The Wrapper vs. The Native

Let’s look at the difference in practice.

The “Bad” Way: The Opaque Wrapper

You are a new engineer on the team. You need to know what kind of disk is attached to a production VM. You find this in the main.tf:

Terraform

# What does this actually deploy? I have to open the module source to find out.

module "prod_web_server" {

source = "./modules/generic_compute_v3"

cloud = "azure"

server_name = "web-01"

flavor = "large"

disk_tier = "fast"

}This code is concise, but it is opaque. What is a “large” flavor in Azure? What does “fast” mean? Is it Premium SSD v1 or v2? To find out, you have to dig into the module code, unpick the variable maps, and trace the logic.

The “Good” Way: Verbose, Native Silos

Now look at the native approach. We accept that AWS and Azure are different, so we write different blocks for them side-by-side in the same state file.

Terraform

# AWS Implementation

resource "aws_instance" "web_server" {

ami = data.aws_ami.ubuntu.id

instance_type = "t3.large"

root_block_device {

volume_type = "gp3"

iops = 3000

}

# ... tags and networking ...

}

# Azure Implementation side-by-side

resource "azurerm_linux_virtual_machine" "web_server" {

name = "web-01"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

size = "Standard_D4s_v5"

os_disk {

caching = "ReadWrite"

storage_account_type = "Premium_LRS"

}

# ... tags and networking ...

}Is this more lines of code? Yes.

Is it infinitely easier to read, understand, and debug? Absolutely.

The native approach is explicit. I know exactly what instance types and disk tiers are being used without consulting a Rosetta Stone of internal module documentation.

The Day 2 Nightmare: Feature Lag

The biggest cost of the Wrapper Tax is paid on “Day 2,” when new features are released.

Imagine AWS announces a new EBS volume type that is 30% cheaper and faster. You want to use it immediately to cut costs.

- If you use Native blocks: You change

volume_type = "gp2"tovolume_type = "gp3"in youraws_instanceresource, run a plan, and apply. Done in 10 minutes. - If you use a Generic Wrapper: You cannot use the feature. The wrapper doesn’t know that the new volume type exists. You have to file a ticket with your internal platform team to update the

generic_computemodule to accept the new input, wait for them to test it to ensure it doesn’t break Azure deployments, version the module, and then you can finally upgrade.

Generic wrappers actively prevent you from leveraging the innovation of the cloud providers you are paying for.

Conclusion: Embrace the Silo

If your organization has decided to use multiple clouds, the engineering reality is that you have multiple distinct infrastructure stacks. Your IaC should reflect that reality, not try to hide it.

Stop trying to pretend that an Azure vNet is the same thing as an AWS VPC. They aren’t.

It is okay to have an aws/ directory and an azure/ directory in your repository. It is okay to use native resources that expose the full power of each platform.

Verbose, explicit code that uses standard, publicly documented resources will always beat concise, clever abstraction layers that require internal tribal knowledge to operate.

Additional Resources: