Your Cloud Provider Is Not Your HA Strategy

This strategic advisory has passed the Rack2Cloud 3-Stage Vetting Process: Market-Analyzed, TCO-Modeled, and Contract-Anchored. No vendor marketing influence. See our Editorial Guidelines.

A Tactical Playbook for Architecting, Testing, and Automating Real Multi-Cloud & Multi-Region Resilience

We’ve previously explored why cloud SLAs fail as guarantees in our deep dive,

Cloud SLA Failure & Resilience Strategy.

This article focuses on how to survive those failures in practice — architecturally, operationally, and financially.

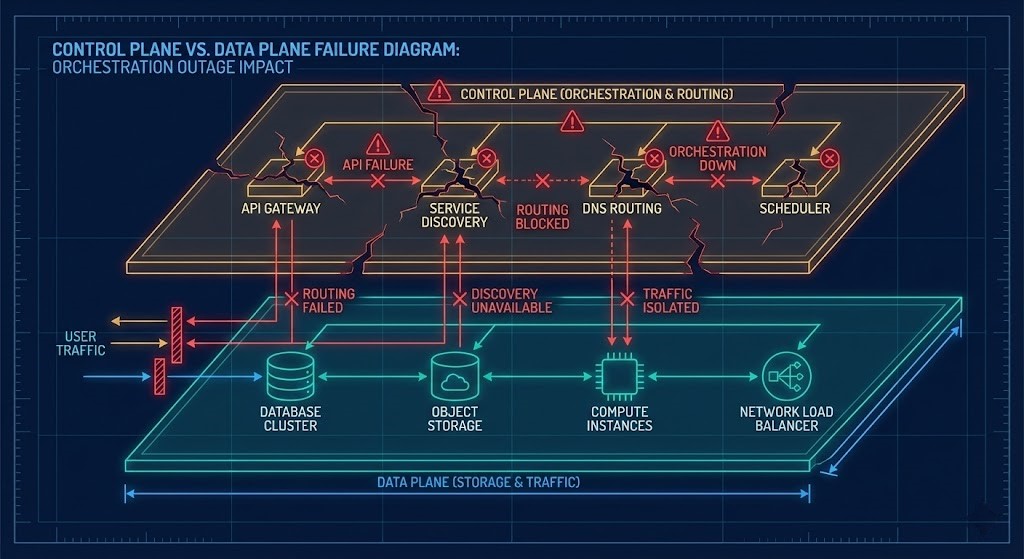

I still get a twitch in my left eye whenever someone says “Availability Zones.” It traces back to a Thanksgiving weekend three years ago when a major hyperscaler suffered a control plane failure in a flagship region. My client—a fintech unicorn—was confident.

“We have Multi-AZ RDS,” they said. “We’re safe.”

They weren’t. The control plane outage meant the orchestration layer responsible for replica promotion was unavailable. The data itself was intact, fully synchronized, and sitting safely on disk. But the application couldn’t reach it because DNS propagation, failover routing, and service discovery all depended on the same control plane APIs that were actively failing. We spent fourteen hours manually modifying host files, tunneling traffic through a temporary VPN mesh, and bypassing managed endpoints entirely.

That night reinforced a truth every senior architect eventually learns the hard way: Availability is not a checkbox. It is a discipline.

If your HA strategy is built entirely on your cloud provider’s SLA, you do not have a strategy. You have a financial insurance policy that pays in service credits while your customers experience downtime, your operations teams burn out, and your executive leadership loses trust in the platform.

Key Takeaways

- SLAs are Financial, Not Technical: A “five 9s” guarantee only promises a refund, not uptime.

- The CAP Theorem is Non-Negotiable: Multi-region active-active requires resolving partition tolerance vs. consistency. You cannot cheat physics.

- Control Planes are SPOFs: Architect for “Data Plane Only” operations during outages.

- Egress is the Silent Killer: Resilience costs multiply not by compute, but by data movement.

The “SLA Math” Trap vs. Engineering Reality

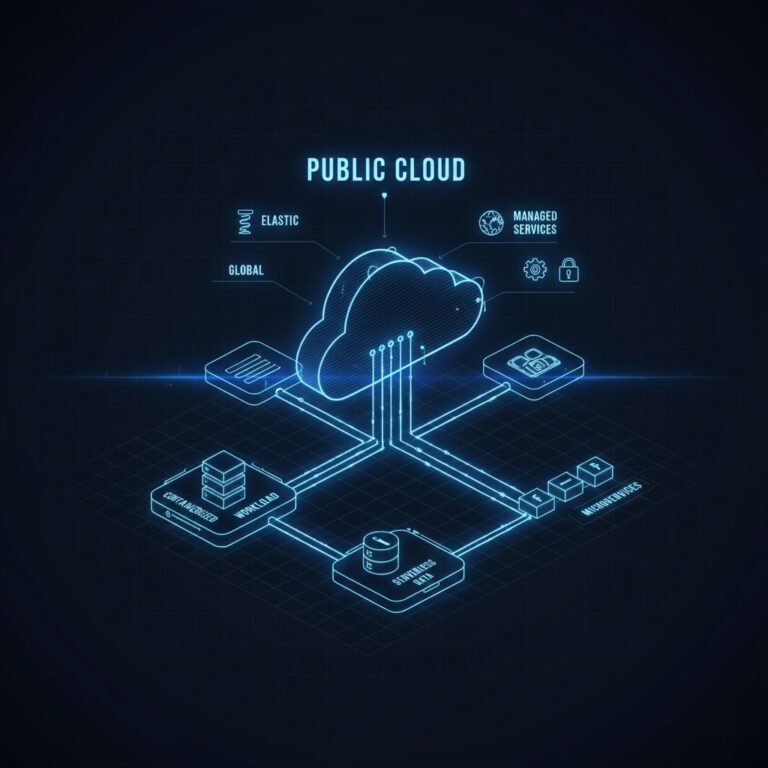

Most organizations conflate availability with reliability—and cloud marketing actively encourages this confusion. Availability is a probability statement about whether an endpoint responds at a given moment. Reliability is a systems property describing whether your application behaves correctly over time under failure conditions. One is a vendor metric. The other is an engineering outcome.

When I design for resilience, I do not ask “How many nines does this service promise?” I ask, “What is the blast radius when it fails?” That shift changes everything—from topology to operational workflows to financial modeling.

Decision Framework: Defining Your Failover Scope

| Scenario | The Trap (Vendor Promise) | The Reality (Architect’s View) | Recommended Strategy |

| Zone Failure | “Multi-AZ handles it automatically.” | Retries storm surviving zones; capacity limits reject failover. | Over-provisioning + Circuit Breakers. Run at 40% across 3 zones—not 50% across 2. |

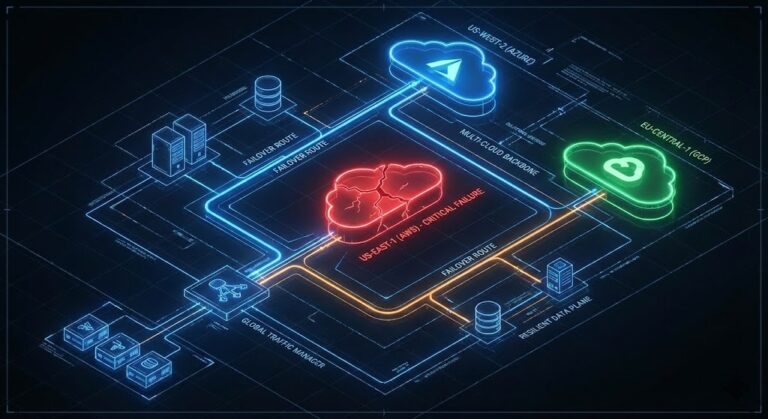

| Region Failure | “Just flip DNS to West.” | Replication lag (RPO > 0). Failover APIs may be global and down. | Async Replication + Pilot Light. Treat DR as a separate system, not an extension. |

| Account Compromise | “IAM policies protect us.” | Lateral movement is instant. A compromised root kills all regions. | Cell-Based Architecture. Isolate workloads into separate accounts/projects. |

CAP Trade-offs: Why Multi-Region Isn’t a Free Lunch

Every multi-region architecture is governed by the CAP theorem—not as an abstract academic idea, but as a hard operational constraint. You cannot simultaneously guarantee consistency, availability, and partition tolerance in a distributed system. You must choose which property degrades under failure.

Most architects implicitly choose availability over consistency without acknowledging the consequences. They design systems that continue accepting writes in both regions during a partition—only to discover later that reconciling divergent datasets is operationally catastrophic.

True global active-active architectures require one of two conditions:

- Your data model must tolerate eventual consistency with conflict resolution logic baked into the application layer.

- Your workload must be sharded by geography, so no two regions write to the same data entities.

If neither is true—and in most enterprise workloads, neither is—then multi-region active-active is not resilience. It is deferred corruption.

Architectural Patterns: Active-Active vs. The Wallet

The industry myth that “active-active is the gold standard” has done more architectural harm than almost any other design trope in cloud computing. In practice, true bi-directional active-active introduces transaction race conditions, write amplification, latency inflation, and exponential testing complexity.

For most workloads, these risks outweigh the outage scenarios active-active is meant to prevent. I recently audited a healthcare platform attempting a bidirectional active-active deployment between Virginia and Frankfurt. They spent six months resolving data races in their persistence layer—only to realize their compliance posture prohibited patient data from leaving its geographic boundary.

The Architect’s Selection Matrix

- Global Active-Active

- Use when: Application is stateless or entity-sharded by region; can tolerate eventual consistency; need ultra-low-latency user access.

- Avoid when: Relying on a centralized transactional datastore or requiring strict consistency.

- Active-Passive (Hot Standby)

- Use when: RTO must be near-zero; full duplicate infrastructure cost is justifiable.

- Trade-off: You pay for a full second environment that sits idle 99.9% of the time.

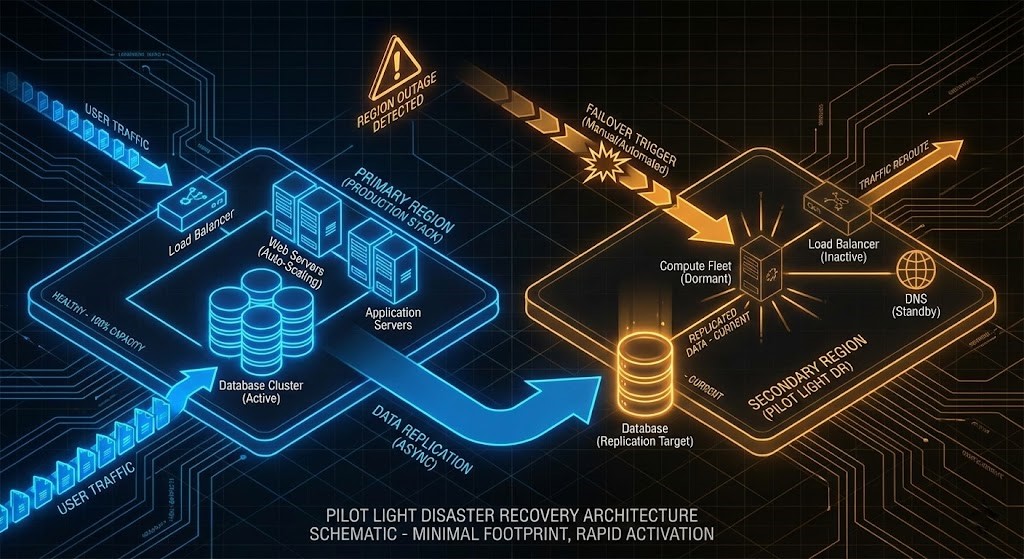

- The “Pilot Light” (Preferred Pattern)

- Strategy: Data replication is continuous, but compute is minimal. Core infrastructure (load balancers, identity) remains deployed, but application compute auto-scales only during failover.

- Result: Dramatically reduced OpEx while maintaining acceptable RTO (often <15 mins).

Control-Plane Failure Mechanics: The Real SPOF

Most architects design for data plane failure—instance crashes, disk corruption, network packet loss. Fewer design explicitly for control plane failure—and that is where the most damaging outages occur.

A control plane failure disables the APIs responsible for DNS propagation, load balancer configuration, and replica promotion. In other words, your data can be perfectly intact, and your infrastructure completely unusable.

The Lesson: You must architect for “data-plane-only” operation during outages.

- Cache DNS locally or in third-party resolvers.

- Maintain alternate access paths (direct IP routing, private interconnects).

- Ensure your application can operate without orchestration APIs for extended periods.

Financial Modeling: CapEx, OpEx, and the Egress Tax

Resilience architecture is fundamentally a financial exercise disguised as a technical one. Most DR initiatives fail not because they are technically unsound, but because they become economically unsustainable once real traffic hits the bill.

Data Egress—The Silent Multiplier

Cross-region replication is charged at network rates. Replicating 50 TB of transactional data across regions can cost more than the entire primary compute stack.

- Mitigation: Compress replication streams, use block-level deduplication, and replicate only deltas.

Licensing—The Legal Trap

Enterprise software licensing can destroy the economics of HA. Many vendors consider a standby node to be “billable” the moment the service process is running—even if it receives zero traffic.

- Strategic Advice: Negotiate DR rights into your enterprise agreements. Alternatively, run open-source equivalents (PostgreSQL, Linux) in the secondary region to avoid license duplication.

Day 2 Operations: If You Don’t Break It, It Won’t Work

A DR plan that lives in a document is not a plan; it is a hypothesis. I require failure injection as a production gate. If your system cannot survive a simulated zone or region failure in staging, it does not ship.

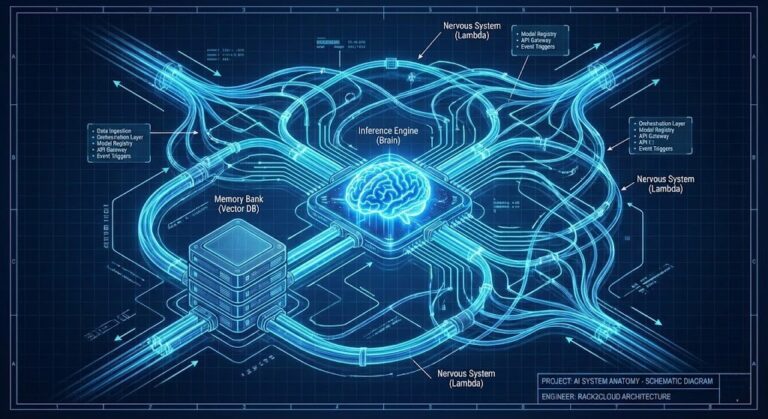

Automating the Panic

We must move from runbooks (humans reading instructions) to run-code (machines executing deterministic workflows).

1. Drift Detection (The “Scheduled Detective”) Don’t wait for a deployment to check state. Run a terraform plan -out=tfplan via a cron job every 4 hours on your DR environment.

- The Compliance Check: Pipe the plan output to our Sovereign Drift Auditor to automatically flag non-sovereign drift and unencrypted storage buckets before they become a compliance violation.

- The Alert: If the auditor returns a non-zero exit code (Drift Detected), fire a high-priority alert to the On-Call channel. Do not auto-remediate. Catch the manual change 5 minutes after it happens, not during the failover.

2. The “Big Red Button” Failover must be a single API call that triggers a state machine. This function must promote replicas, update DNS, and scale compute. We rely heavily on Deterministic Tools for a Non-Deterministic Cloud for this exact workflow.

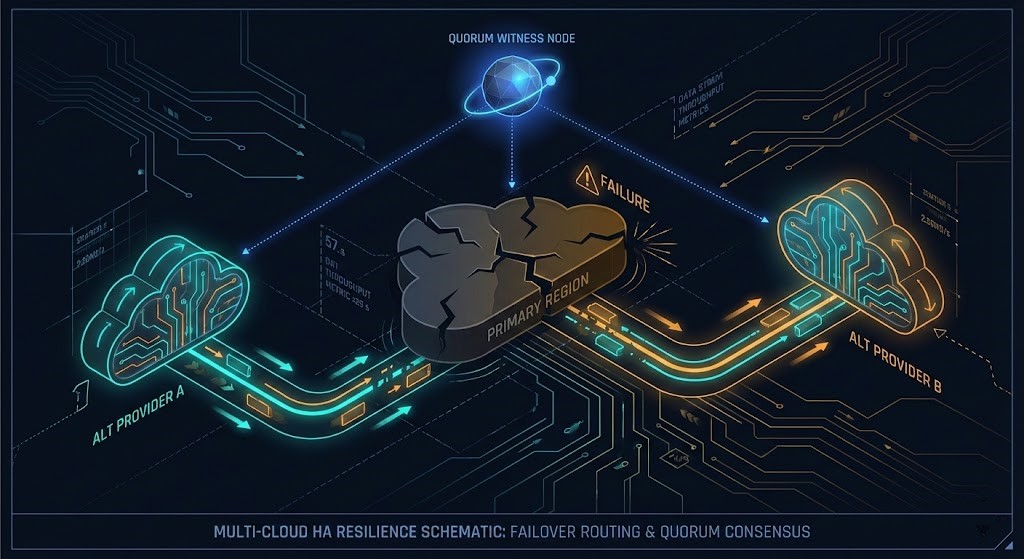

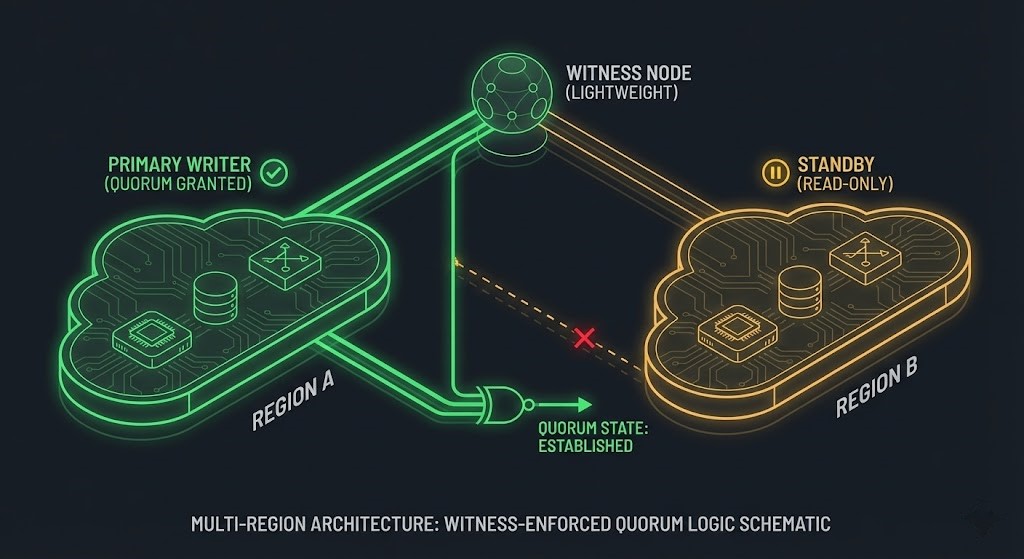

Quorum Theory: Preventing the Split-Brain Catastrophe

The most dangerous failure mode in distributed systems is not downtime; it is inconsistent writes. If two regions lose connectivity and both believe they are primary, you have a data integrity crisis.

To prevent this, you must enforce Quorum—a majority decision model.

- The Witness Pattern: Use a third “Witness” region (minimal footprint) to act as a tie-breaker.

- Logic: A region may declare itself leader only if it can see either the other region OR the witness.

- Tech: Use Etcd, Consul, or ZooKeeper to manage this state outside your application database.

Conclusion

Your cloud provider builds data centers; you build systems. They own concrete and cables; you own correctness and continuity.

Stop chasing uptime percentages in marketing decks. Start engineering for graceful degradation. It is better to serve stale data than corrupted data.

Think like an architect: Design for failure. Build like an engineer: Automate the recovery.

Additional Resources

- Google SRE Book: The Calculus of Service Availability

- AWS Well-Architected Framework: Reliability Pillar

- Martin Fowler: Patterns of Distributed Systems (Quorum)

This architectural deep-dive contains affiliate links to hardware and software tools validated in our lab. If you make a purchase through these links, we may earn a commission at no additional cost to you. This support allows us to maintain our independent testing environment and continue producing ad-free strategic research. See our Full Policy.