The Physics of Data Egress: Why “Cloud First” Fails Without a TCO Reality Check

This strategic advisory has passed the Rack2Cloud 3-Stage Vetting Process: Market-Analyzed, TCO-Modeled, and Contract-Anchored. No vendor marketing influence. See our Editorial Guidelines.

I still remember the call at 2:00 AM in 2018. A Fortune 500 client was panicking because their AWS bill had spiked 300% overnight. The culprit wasn’t a crypto miner or a DDoS attack; it was their own data team. Unmonitored egress from S3 to on-prem analytics pipelines had been left open during a quarterly close. We killed the transfers, but not before $180,000 vanished into the AWS egress black hole.

That incident crystallized something we at Rack2Cloud have argued for over a decade: data egress isn’t just bandwidth — it’s where physics meets economics. If you ignore the mass, velocity, and dependency of your data, you don’t just risk inefficiency. You risk architectural insolvency. This is exactly why we built our Deterministic Tools for a Non-Deterministic Cloud — to expose and constrain these hidden failure economics before finance does.

Key Takeaways

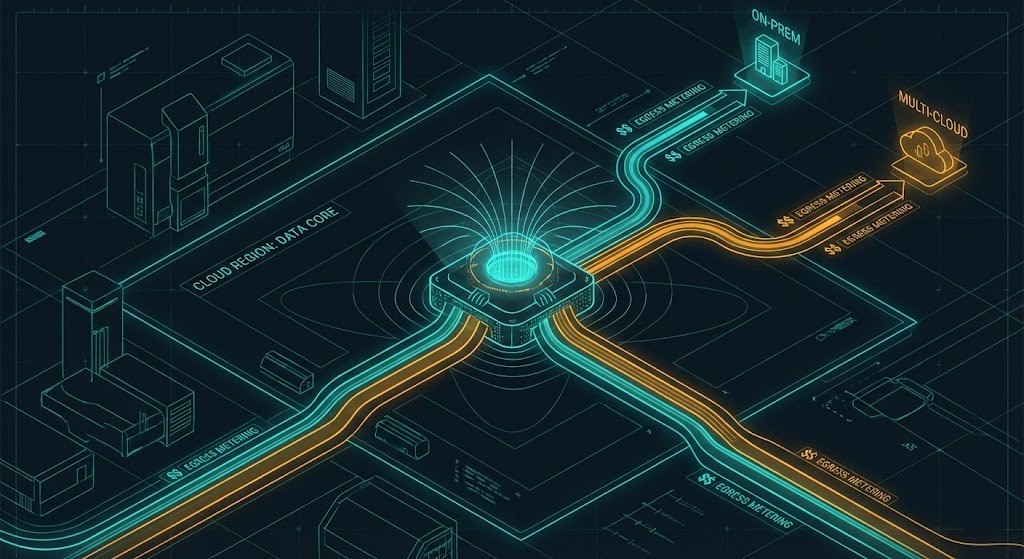

Data egress follows physical laws disguised as pricing models. Large datasets don’t merely cost more to move — they exert a kind of gravitational pull that reshapes your entire architecture. What looks like a “minor” replication pipeline becomes, at scale, the dominant driver of operational cost.

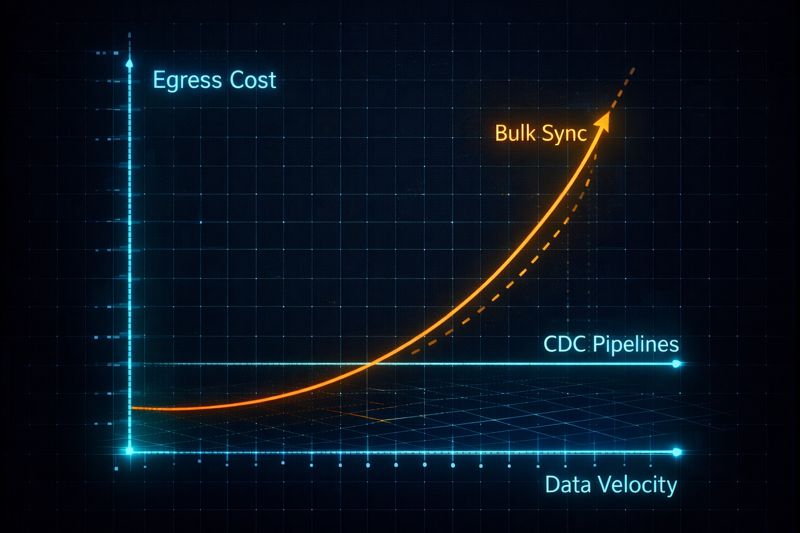

Cloud providers often advertise egress as “pennies per gigabyte,” but that framing hides the reality that egress compounds with velocity, retries, dependency chains, and licensing constraints. In practice, the cost curve is exponential, not linear.

Interconnects, intra-region replication, and CDC pipelines are not optimizations — they are architectural survival tools. Without them, high-velocity systems bleed money in the background, invisible until finance calls at 2:00 AM.

Egress Fundamentals: The Physics of “Gravity”

Data egress obeys physical constraints in much the same way gravity does: the more mass you accumulate, the harder it becomes to move. Cloud vendors invert this natural law by amplifying cost as distance and velocity increase. I model this using a simple heuristic:

Egress Gravity=Volume×Dependency×Velocity

Volume is obvious — terabytes become petabytes faster than teams expect. Dependency is the hidden multiplier: every downstream system that requires that data increases the cost of movement and the blast radius of failure. Velocity is the real killer. Static archives are cheap to move once. Streaming systems never stop moving, and therefore never stop billing.

Vendor white papers often claim that compression solves this problem. In real-world systems, it rarely does. Compression works on bulk, low-change datasets. It fails spectacularly on high-velocity streams — log ingestion, CDC replication, ML inference telemetry — where the entropy of change is high and the window for batching is low. In those environments, compression reduces size marginally but does nothing to address the fundamental physics of continuous movement.

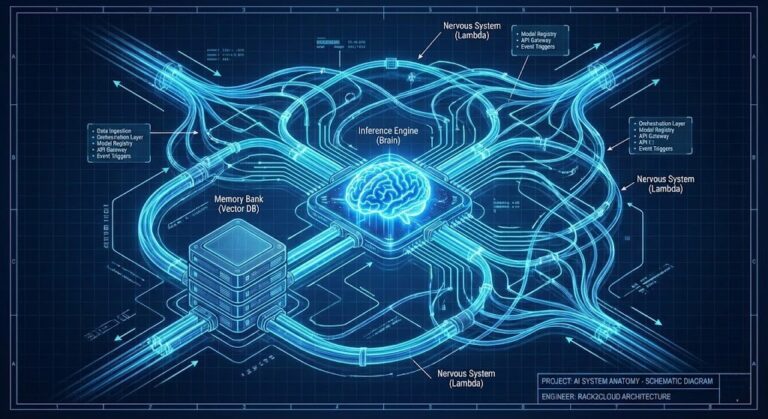

This is why CDC architectures matter. They don’t compress the data — they eliminate unnecessary movement by transmitting only the semantic delta. This is the same design philosophy we apply in our Lambda Cold Start Optimization work: minimize cold paths, eliminate unnecessary state movement, and collapse cost into deterministic flows.

The Bandwidth Throttle

Even if money were no object, bandwidth remains a hard ceiling. A 10Gbps link, under perfect conditions, caps at roughly 1.25 GB/s. That means a 500TB dataset requires a minimum of 112 hours to transfer — and that assumes zero packet loss, no retries, no throttling, and no competing workloads.

In practice, real-world throughput is lower. TCP backoff, encryption overhead, NAT traversal, and transient congestion all degrade effective bandwidth. This is why we never trust vendor calculators when planning migrations. We baseline with iperf3 in isolated environments to measure actual sustained throughput under production-like conditions before committing to timelines or budgets.

Bandwidth throttles do more than slow migrations — they extend cost exposure windows. Every hour a transfer runs is another hour of metered egress. Physics doesn’t just constrain speed; it compounds financial risk.

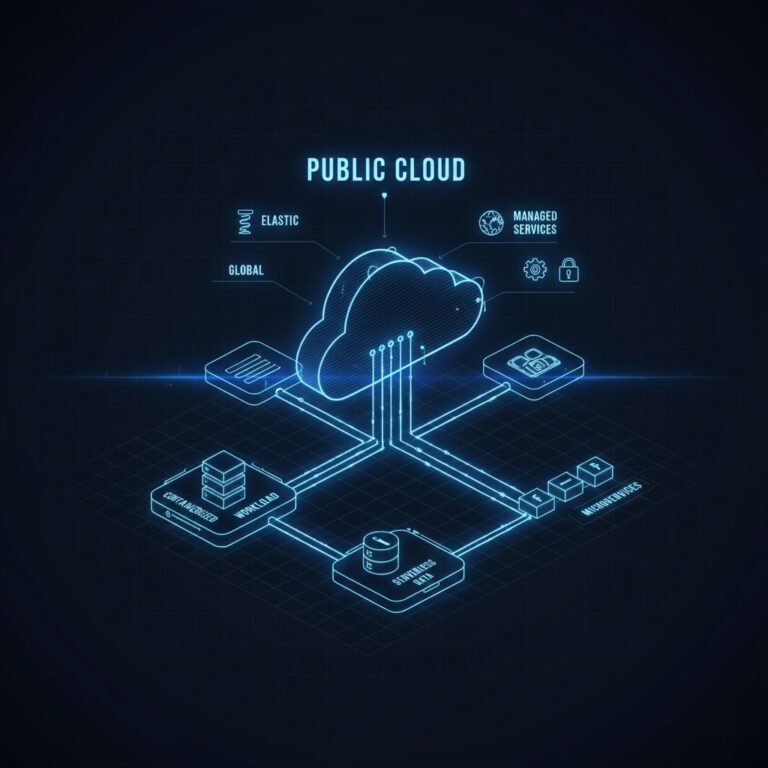

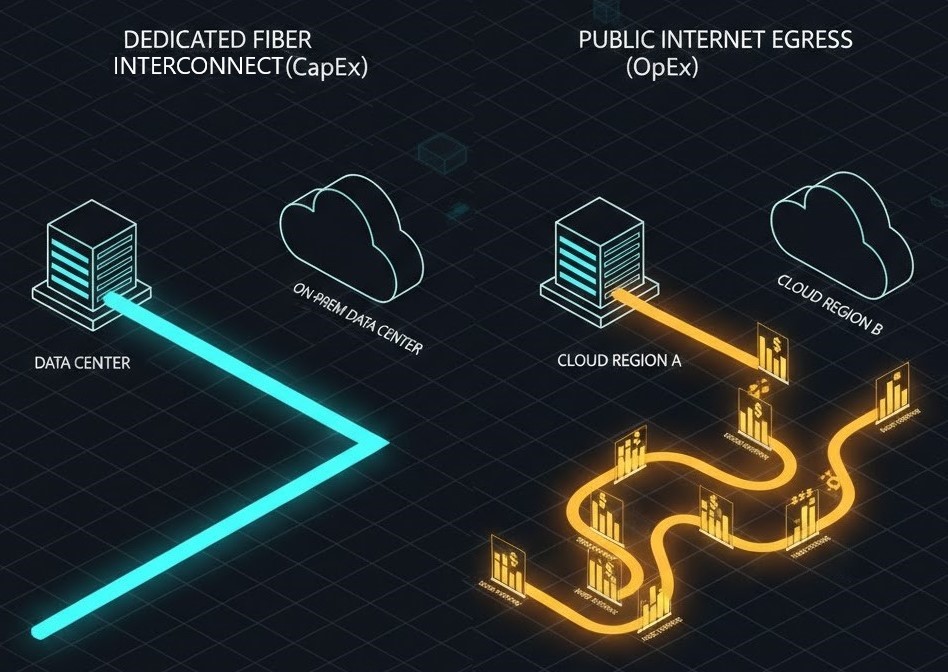

Economic Forces: CapEx vs. OpEx

In the data center, you pay for the pipe. In the cloud, you pay for the liquid flowing through it. This inversion fundamentally alters how architects must think about infrastructure economics.

With dedicated interconnects — AWS Direct Connect, Azure ExpressRoute, or Google Cloud Interconnect — you incur upfront port fees and commit to capacity. But once provisioned, data movement becomes effectively amortized. You pay for the pipe whether you use it or not, which means marginal transfers approach zero cost.

Public internet egress flips that model. There is no upfront commitment, but every gigabyte is metered. At scale, this becomes punitive. A single petabyte of annual transfer at AWS public egress rates exceeds $90,000 — and that’s before retries, replication overhead, or multi-destination fan-out.

Architecturally, this forces a choice: do you want predictable CapEx with bounded risk, or unbounded OpEx with unpredictable failure exposure? At Rack2Cloud, we treat this not as a financial decision but as a reliability one. This exact tradeoff shows up repeatedly in our Modern Infrastructure & IaC Path — where cost stability and failure domains matter more than raw service features.

The Licensing Trap

Egress is not just a network problem — it’s a licensing problem disguised as one.

Many enterprise software licenses count data movement as usage. VMware vMotion charges per-VM hops across clusters. Oracle and SQL Server often require full licensing for standby replicas, even if they are passive. Some vendors treat DR replicas as production instances for billing purposes the moment they receive write traffic.

This turns hybrid and multi-cloud architectures into legal minefields. Teams optimize network topology only to discover that the licensing model negates the savings — or worse, creates compliance risk.

Our internal rule is blunt: if licensing overhead causes egress-related OpEx to exceed 5% of total system TCO, the architecture must be rewritten. That usually means replacing proprietary platforms with open formats and open-source runtimes in secondary regions — PostgreSQL instead of Oracle, Parquet instead of proprietary storage, Linux instead of commercial UNIX. This philosophy directly aligns with our Virtualization Strategy Pillar, where exit cost, not feature richness, determines platform viability.

Architecture Decisions & Real-World Migrations

When designing for Day 2 operations, “features” matter far less than the cost of exit. The most dangerous architectures are not the ones that fail loudly — they are the ones that succeed expensively.

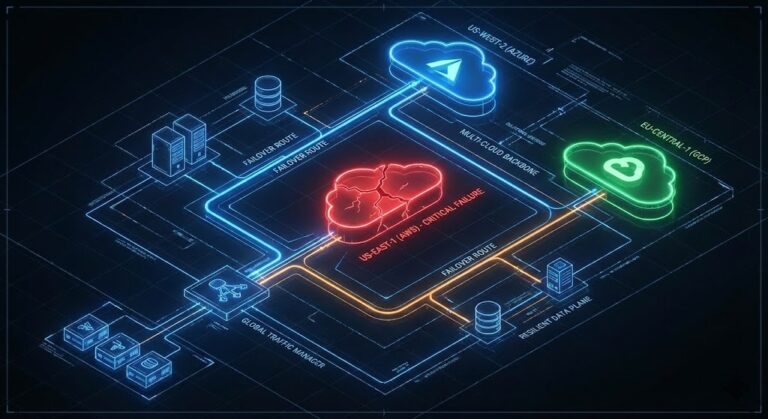

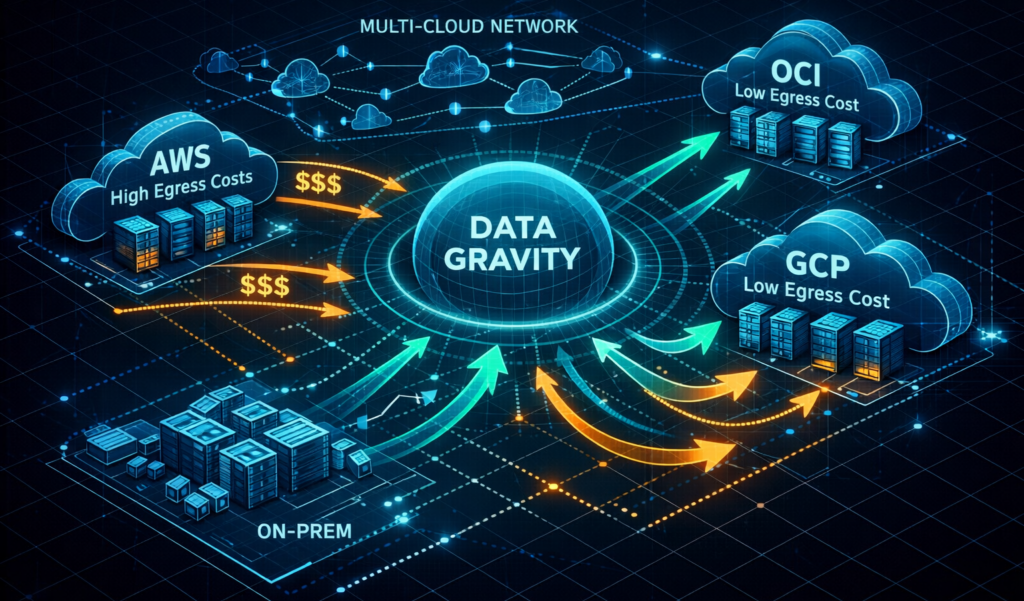

In multi-cloud environments, provider selection must be driven by data movement economics, not marketing. OCI and GCP offer near-zero egress for intra-region and inter-service movement, which makes them structurally superior for data gravity workloads — analytics, AI pipelines, and backup fabrics. AWS remains indispensable for latency-sensitive workloads, edge integrations, and service breadth, but it is rarely the optimal home for high-volume data mobility.

This creates a natural hybrid pattern: compute where latency matters, data where gravity dominates. The mistake teams make is allowing vendors to offer “free egress” as a lure — only to trap data inside proprietary storage formats, APIs, or managed services that eliminate portability. Egress is only free if your data can actually leave.

This is why we enforce open formats — Parquet, ORC, Avro — and open replication protocols — CDC, Kafka, Debezium — as architectural guardrails. Portability is not an afterthought; it is the foundation of economic resilience.

Case Study: The 2PB Escape

We recently managed a 2-petabyte migration for a financial services client exiting AWS for OCI. Their original architecture relied on nightly S3 exports and batch syncs to downstream systems, which created massive egress spikes during quarterly close cycles.

We replaced bulk replication with CDC using Debezium, reducing transfer volume by 92%. High-velocity transactional changes were streamed in near real-time, while cold historical data was migrated via dedicated fiber.

The result was not just faster — the entire migration completed in under 48 hours — but dramatically cheaper. Compared to direct public egress, the client avoided approximately $250,000 in transfer fees alone.

In contrast, a retailer attempting an unoptimized S3-to-Azure lift burned over $60,000 per week until we intervened and re-architected their replication layer using our Modern Infrastructure & IaC Path.

The difference between those outcomes was not tooling. It was physics awareness.

Cost Optimization Framework

If your organization is bleeding money today, you don’t need a strategy deck — you need a triage protocol.

Start by auditing velocity, not volume. Use CloudWatch Logs Insights, VPC Flow Logs, or equivalent telemetry to identify any data movement exceeding 1TB per day. These are your economic hemorrhages.

Then enforce Day 2 observability. Your monitoring system must scrape egress metrics — not just network throughput, but billable transfer. Alerts should trigger on cost deltas, not bandwidth deltas. We embed these guardrails directly into Terraform modules to prevent the “surprise bill” phenomenon. This approach is fully documented in our Infrastructure Drift Detection Guide.

Next, model total cost of ownership using a realistic formula:

(Volume×Rate×Frequency)+(Retry Factor≈1.2)

Retries, partial failures, and backoffs are not edge cases — they are the steady-state behavior of distributed systems.

Finally, negotiate. If you hold an Enterprise Agreement, egress caps are often available — but never advertised. We have successfully negotiated AWS egress rates down to $0.05/GB post-100PB, but only because we approached the vendor with empirical usage models and a credible exit plan.

The Strategic Truth

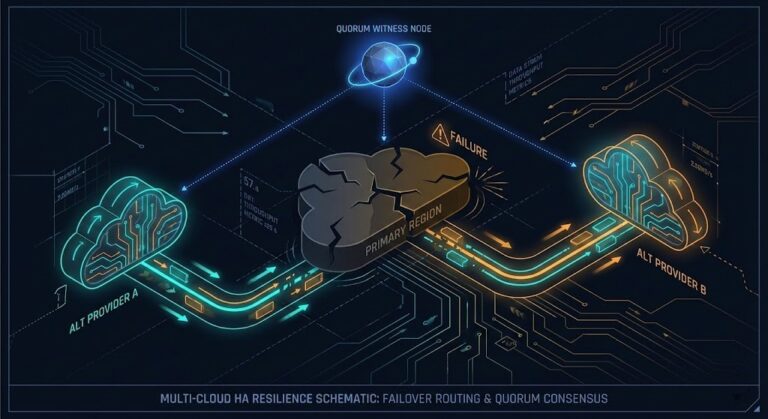

High availability is not achieved by redundancy alone. It is achieved by minimizing the economic friction of failure.

When your system fails, data must move — to another region, another provider, another environment. If that movement is slow, expensive, or legally constrained, recovery becomes not just delayed, but economically irrational. At that point, your architecture has failed before your servers have.

Cloud providers build data centers. You build physics-aware systems.

If you ignore the gravity of your data, it will eventually pull your budget — and your architecture — into a collapse you didn’t see coming.

Architect’s Verdict: Physics Always Wins

Cloud cost overruns rarely come from bad engineers — they come from bad assumptions. The most dangerous assumption in modern architecture is that data movement is cheap, reversible, or operationally trivial. It is none of those.

Data has mass. Movement has friction. Dependencies have gravity. When failure occurs — and it always does — your recovery speed is bounded not by your redundancy but by your ability to move state across domains. If that movement is slow, expensive, or contractually constrained, your system is not resilient — it is brittle with a delay.

Architects must therefore design not for uptime, but for economic survivability under failure. That means:

- Data must be portable before it is replicated.

- Recovery paths must be affordable before they are automated.

- Exit must be possible before entry is approved.

High availability is not a topology. It is an economic property of your system under stress. If your architecture cannot afford to fail, it cannot be trusted to succeed.

Physics always wins. Design accordingly.

Additional Resources

- AWS Direct Connect Pricing: Verification of port fees vs transfer rates. AWS Pricing

- Debezium CDC: The standard for low-latency, low-overhead data mobility. Debezium.io

- Oracle Cloud Networking: Validation of OCI’s non-blocking networks and egress pricing. OCI Networking

This architectural deep-dive contains affiliate links to hardware and software tools validated in our lab. If you make a purchase through these links, we may earn a commission at no additional cost to you. This support allows us to maintain our independent testing environment and continue producing ad-free strategic research. See our Full Policy.