CPU Ready vs. CPU Wait: Why Your Cluster Looks Fine but Feels Slow

The Reality Check: “Everything is Slow, But the Dashboard Says 30%”

You know the ticket. “The application is sluggish.” You pull up Prism Element or vCenter. You look at the cluster average CPU usage. It’s sitting at a comfortable 35%. You check the specific VM. It’s idling at 20%.

You close the ticket: “Infrastructure looks fine. Check your code.”

Two hours later, the CIO is at your desk because the CFO’s report took 40 minutes to generate instead of 4. You didn’t look deep enough. You looked at consumption, not contention. In a virtualized world, “usage” is irrelevant if the processor can’t get time on the physical core.

This is the silent killer of virtualization: CPU Ready (or Steal, or Co-Stop). It’s why your “powerful” 32-vCPU SQL server is running slower than a laptop.

The Mechanics: The vSMP Scheduler & The “Tetris” Problem

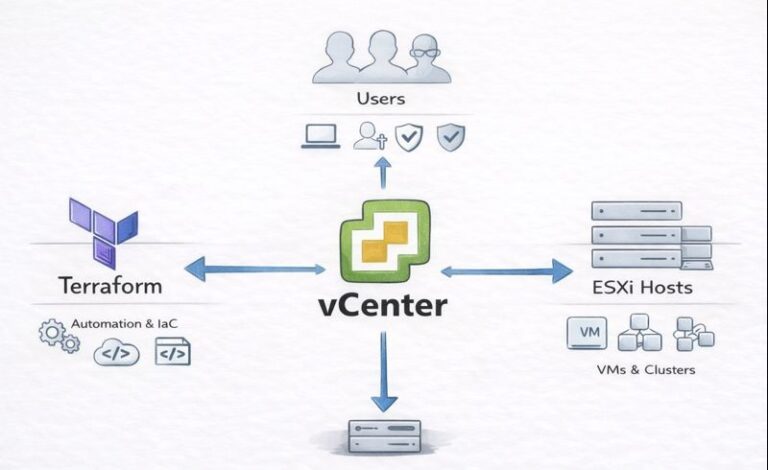

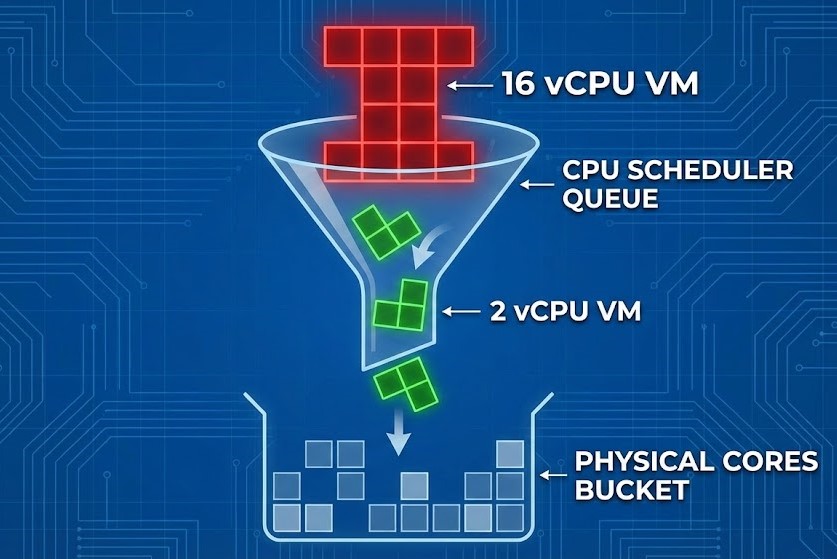

The hypervisor (whether ESXi or AHV) is a traffic cop. It doesn’t “give” CPU to a VM; it schedules time slots on physical cores.

The “Right-Sizing” Paradox

Junior admins think “More vCPUs = More Speed.” This is false. It is the opposite of physics.

If you assign 24 vCPUs to a VM on a host with 28 physical cores, the scheduler has to find 24 physical cores that are free at the exact same nanosecond to execute a cycle. This is Co-Stop (%CSTP in ESXi). While the scheduler waits for those 24 lanes to clear, your VM sits frozen. It is “Ready” to process, but it is waiting.

The Metric That Matters:

- CPU Ready (%RDY): The time the VM wanted to run but the hypervisor said “Wait your turn.”

- Threshold: If this is >5% per vCPU, your users are suffering. If it’s >10%, your application is broken.

Caption: The “Tetris” Problem: Large VMs wait longer for a free slot than small VMs.

The Noisy Neighbor & The Pool

This gets worse in shared pools. If you have a developer spinning up 50 microservices on the same host as your production database, and they are all fighting for the same L3 cache and physical cycles, your pooling physics break down. The hypervisor spends more time context-switching (loading/unloading CPU registers) than actually computing.

The Solution: The HCI Handshake (Don’t Starve the CVM)

Hyper-Converged Infrastructure (HCI) adds a layer of complexity that legacy 3-tier architects miss. In Nutanix (AHV) or vSAN, the storage controller is a VM (CVM). It needs CPU to process I/O.

If your host is saturated with high %RDY, the CVM also waits for CPU time. The result? High CPU Ready causes High Storage Latency. The application team sees “Disk Latency” and blames storage. You buy more SSDs. The problem persists because the SSDs are fast—the CVM just couldn’t get the CPU cycles to acknowledge the write.

Diagnosing the Freeze

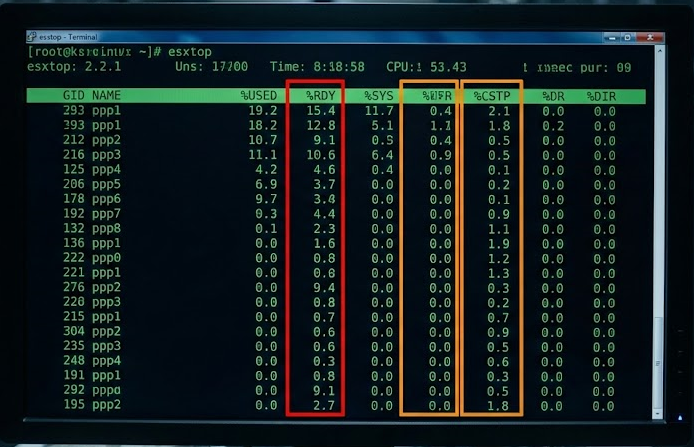

Don’t trust the GUI averages. You need raw kernel metrics.

For ESXi (The Gold Standard):

Bash

# SSH into the host. Do not run during backups.

esxtop

# Press 'c' for CPU view.

# Shift + 'V' to only show running VMs.

# Look at the %RDY column.

Caption: The Smoking Gun: Any number over 5.0 in the %RDY column means your VM is gasping for air.

- Formula:

%RDY / 100 * (Update Interval)(Roughly). If the number is huge, look at%CSTP. High CSTP means you gave the VM too many vCPUs. Downsize it.

For AHV (The Linux Approach): AHV is KVM-based. We look at “scheduler wait time.”

Bash

# SSH into the CVM

hostssh "top -c | grep qemu"

# Or use the specific AHV monitoring tool

# Check for 'steal' time in the guest OS

# On the Guest VM (Linux):

top

# Look at the "%st" (steal) value in the CPU row.

If %st is non-zero, the hypervisor is stealing cycles from your VM to serve someone else (or itself).

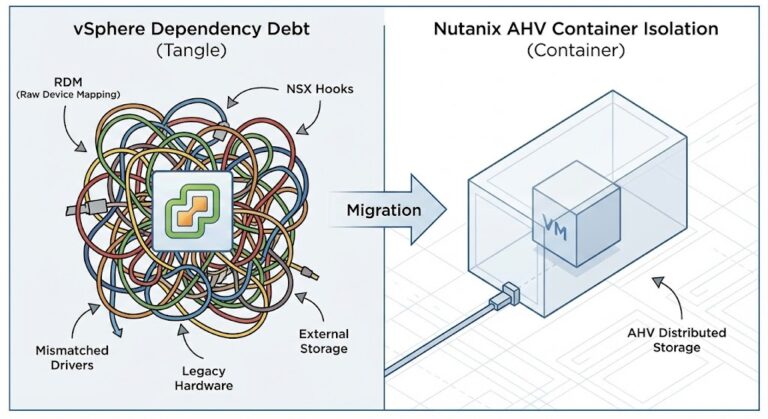

The Migration Trap (vSphere -> AHV)

When executing a vSphere to AHV migration, do not just “Lift and Shift.” VMware’s scheduler is slightly more forgiving of “oversized” VMs than KVM due to different co-scheduling algorithms (relaxed vs. strict). A 12-vCPU VM that “ran fine” on ESXi might choke on AHV if you don’t right-size it during the move.

Use the migration as an excuse to audit. If a VM averages 15% utilization but has 8 vCPUs, cut it to 4 vCPUs. You will actually increase performance.

The Verdict

We treat CPU like an infinite bucket. It isn’t. It is a time-share condo. If everyone tries to use the pool at 2 PM, nobody swims.

My 3 Heuristics for CPU Management:

- The “2-vCPU” Rule: Start every new VM with 2 vCPUs. Prove you need more. I require screenshots of CPU ready <1% and Utilization >80% before I grant more cores.

- The “Numa” Law: Never size a VM larger than a single NUMA node (physical socket). If your server has 14 cores per socket, your max VM size is 14 vCPUs. Cross the NUMA boundary, and you introduce memory latency that ruins the CPU gains.

- The “Ready” Alarm: Set your monitoring (Prism/vCenter) to alert on

%RDY > 500ms(summation) or5%. Ignore “Usage.” Usage is vanity; Ready is sanity.

Stop throwing hardware at “slow.” Start taking vCPUs away. Your cluster will thank you.

Additional Resources

- VMware KB: Troubleshooting CPU Ready – The bible for %RDY calculations.

- Nutanix Bible: AHV Scheduler & Resource Management – Deep dive on AHV’s KVM roots.

- Red Hat KVM Tuning: Understanding Steal Time – Validates the Linux/AHV steal time concepts.

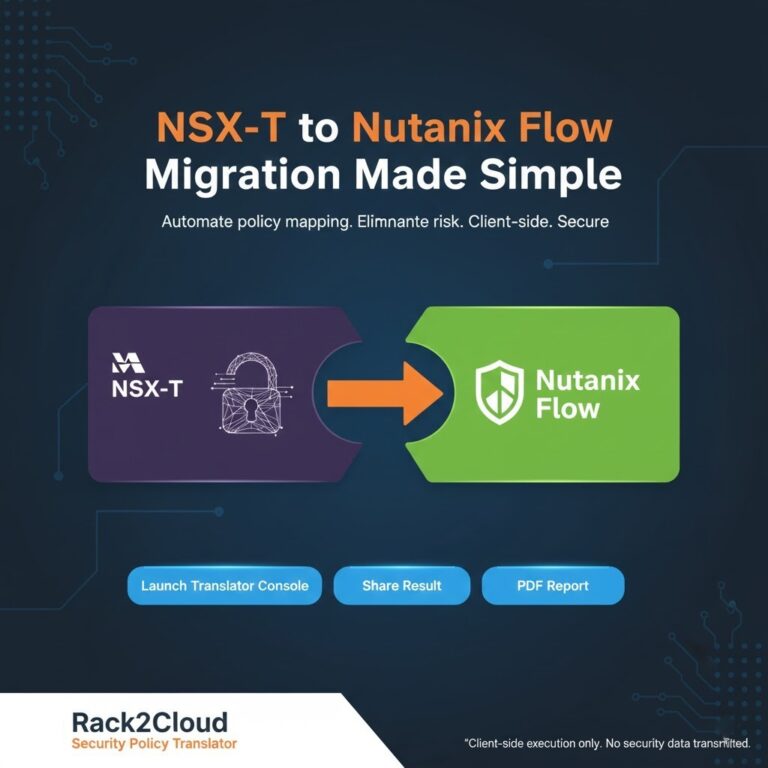

Editorial Integrity & Security Protocol

This technical deep-dive adheres to the Rack2Cloud Deterministic Integrity Standard. All benchmarks and security audits are derived from zero-trust validation protocols within our isolated lab environments. No vendor influence.

This architectural deep-dive contains affiliate links to hardware and software tools validated in our lab. If you make a purchase through these links, we may earn a commission at no additional cost to you. This support allows us to maintain our independent testing environment and continue producing ad-free strategic research. See our Full Policy.